Gender, Language, and Emotions in Chosŏn Korea – In Commemoration of JaHyun Kim Haboush’s Scholarship and Teaching

May 6, 2022

8:30 AM – 4:00 PM EDT | 9:30 P.M. – 5:00 A.M. KST

Elliott School of International Affairs, Room 212 AND Online via Zoom

May 7, 2022

8:30 AM – 11:45 AM EDT | 9:30 PM – 12:45 AM KST

Elliott School of International Affairs, Lindner Family Commons, Room 602 AND Online via Zoom

NOTE: All non-GW affiliated attendees attending the event IN-PERSON must comply with GW’s COVID-19 policy in order to attend this event, including showing proof of vaccination. While masks are no longer required, it is highly encouraged indoors. For frequently asked questions, please refer to GW’s guidance.

Event Description

In order to remember the tenth anniversary of Professor JaHyun Kim Haboush’s death in 2021, the GW Institute for Korean Studies has organized a signature conference to convene scholars of Chosŏn history and literature to commemorate Haboush’s scholarship and teaching. During the past two decades, scholars inspired by Haboush’s scholarship expanded the Chosŏn field by exploring relatively understudied areas such as gender, emotions, epistolary practices, vernacular language, and military history. On the first day of the conference, scholars will present their research that reflects Haboush’s scholarship. On the second day of the conference, two roundtable discussions will focus on Haboush’s scholarship and teaching. By bringing scholars from North America, Europe, South Korea, and Taiwan, the conference also aims to revisit the state of the field and examine new approaches to researching and teaching Chosŏn Korea.

Keynote Speakers

Marion Eggert

Professor of Korean Studies, Ruhr University Bochum

Dorothy Ko

Professor of History at Barnard College, Columbia University

Speakers

Ksenia Chizhova

Assistant Professor of Korean Literature and Cultural Studies, Princeton University

Key-Sook Choe

Professor of Korean Literature at the Institute of Korean Studies, Yonsei University

Byung-Sul Jung

Professor of Korean Literature, Seoul National University

Ji-Young Jung

Professor of Women’s Studies, Ewha Womans University

Jisoo M. Kim

KF Associate Professor of History, International Affairs, and East Asian Languages and Literatures, George Washington University

Suyoung Son

Associate Professor in the Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University

Hyun Suk Park

Assistant Professor of Korean Literature, University of California, Los Angeles

Scholarship Discussants

Martina Deuchler

Emerita Professor of Korean Studies at SOAS, University of London

Masato Hasegawa

Assistant Professor of History, National Taiwan University

George Kallander

Professor of History, Syracuse University

Jungwon Kim

King Sejong Associate Professor of Korean Studies, Columbia University

Young-Key Kim-Renaud

Professor Emeritus of Korean Language and Culture and International Affairs, George Washington University

Boudewijn Walraven

Professor Emeritus of Korean Language and Literature, Leiden University

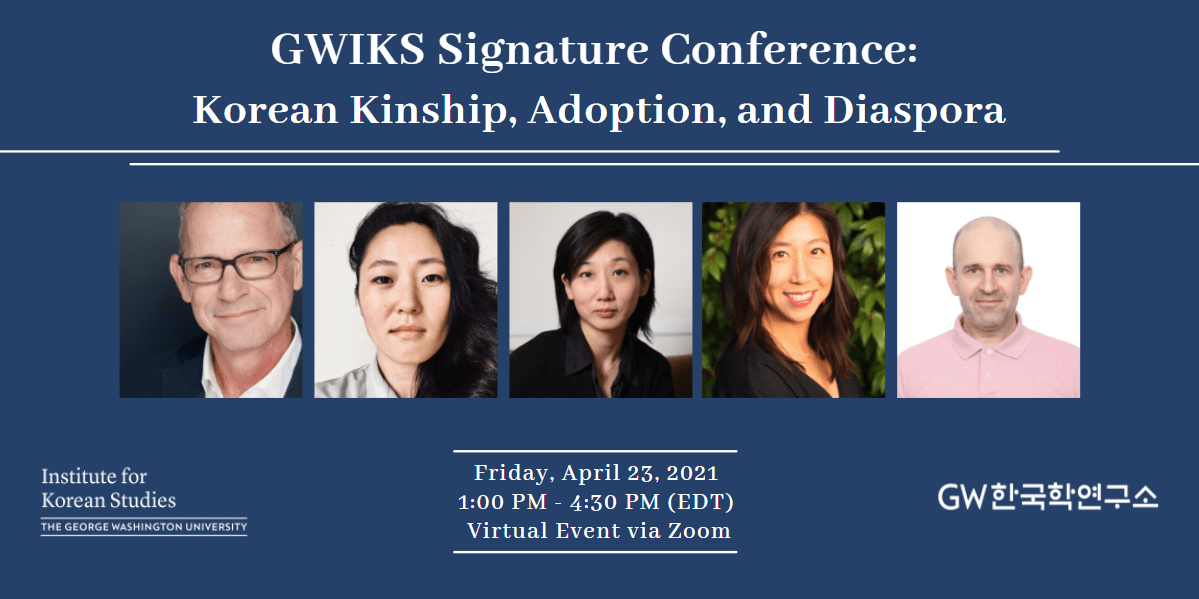

Pedagogy Discussants (Left to Right)

-Li Chen, Associate Professor of History and Law, University of Toronto

-Hwisang Cho, Assistant Professor of Korean Studies, Emory University

-Eleanor Hyun, Associate Curator for Korean Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

-Janet Yoon-Sun Lee, Associate Professor of Korean Literature, Keimyung University

-Sixiang Wang, Assistant Professor of Korean History, University of California, Los Angeles