On January 25th, GWIKS hosted a webinar as part of their Soh Jaipil Lecture Series and was joined by guest speaker Dr. Joan Cho, professor of East Asian Studies and Government from Wesleyan University. Dr. Cho discusses, her book manuscript, “Dictator’s Modernity: Development and Democracy in South Korea, 1961 – 1987.” Reflecting back on the pro-war period, Dr. Cho walks us through a reexamination of the democratization process of Korea and the economic industrialization to come out of it into the modern era.

Korean Democratization: The “Dream Case.”

In reviewing the overall positive progression of South Korea’s rise to democratic governance and economic stability, Dr. Cho urges us to rethink and reanalyses the case of South Korea’s democratization that has been coded as an overall “dream case” of success due to its linear progression since the 1960s. On a national level, most of the evidence evaluating South Korea’s democratization is supportive of the theory of democratization, which states that as states become more industrialize and experience economic prosperity, they become more democratized in their governance and policy. When looking at this case on a sub-national level, however, we actually see variations that suggest that both the economic development and democratization process were temporal and not as parallel in progression as one would think:

Major economic development was focused on benefiting the wealthy and influential people of status and government.

Coming out of the Korean War, President Park Chung Hee put a heavy emphasis on an “Economy First” policy that primarily focused on economic development taking precedent over political progression during authoritarian rule. With this came Export Oriented Industrial Strategy that was put into place to help facilitate South Korea’s economic development that carried on throughout Presidencies.

First five years of this strategy was dedicated to Light Manufacturing as part of 1960’s export plan. Next five years covered the emergence of HCI drives with the development of chaebols, or large industrial conglomerates such as Hyudai and Samsung.

These strategies relied on many domestic resources, prompting the development of Industrial Complexes (ICs) across the peninsula. In the 1960s this would start out as inland cities and slowly progress out to coastal areas in the 1970s with the heavy chemical industrial drive. Finally, in the ’80s other arenas lacking their own Industrial complexes gained developments to make up for the uneven distribution of industrialization in addition to pressures faced by the Labor Movement.

Those who supported regime change to democracy were those within urban settings of the country as much of the rural inhabitants supported the ruling regime at the time.

Those who lived closer to the Industrial Complexes became more supportive of the ruling regime as economic growth diffused political discontent and allowed the regime to buy legitimacy through economic progression. However, these effects would be temporary and became weaker and smaller progressively, as support only seemed to grow during the appointment of a new IC and not during the development nor completion of one with an area.

The working class in the short term were supportive of the ruling regime under the propaganda that those who contributed to the economic growth through laboring within these factories and IC’s were the “pillar and warriors” of South Korea’s modernization movement, as quoted by President Park. The long term effect would inevitably result in the gradual rise of labor disputes and discontent as Park’s rule became more authoritarian in the 1970s. Park began taking a domestic security approach of labor exclusion and repression against the working class as time progressed to continue maximizing economic development despite grievances becoming more prevalent. This includes:

– Suspending workers’ rights to bargain collectively and to engage in collective action

– Reconfiguring the Union structure from industrial to an enterprise union system

– And increased reliance on security forces (police, military, and KCIA) to keep order and labor under control.

Pro-Democratic protests were concentrated in a few cities, mainly in or around Seoul, with nationwide protests not kicking off until 1987.

The long term effects of it all would lead to the first nationwide protest and the largest protest to encapsulate the Labor Movement and the “Great Work’s Struggle,” to come in 1987 were 1.28 million workers ( a third of Korea’s working class) from the peninsula’s most prominent industrials (mining, transportation, service, and manufacturing). These works took to the streets to demand not only demand economic equality throughout the country but also demand a democratized workplace to liquidate state-corporate unions and allow democratic and independent unions to exist on behalf of the workers’ safety and wellbeing.

Through closer examining this case on a deeper level, Dr. Cho’s examined the finite and historical details of how economic development through industrialization impacted the process of democratization, mainly the durability of the authoritarian regime of time. The authoritarian industrial policies that were implemented created a centralized pattern of industrialization that was concentrated, to be used as mediators to labor activism, resulting in the organization and politicization of workers to bring about economic growth and democratization close together. This overall analysis not only expands the perceptions of South Korea’s democratization story but also shows that democratization is not a linear process, with ups and downs that require action to ensure it continues through the fine line of authoritarian to the democratic transition of a state.

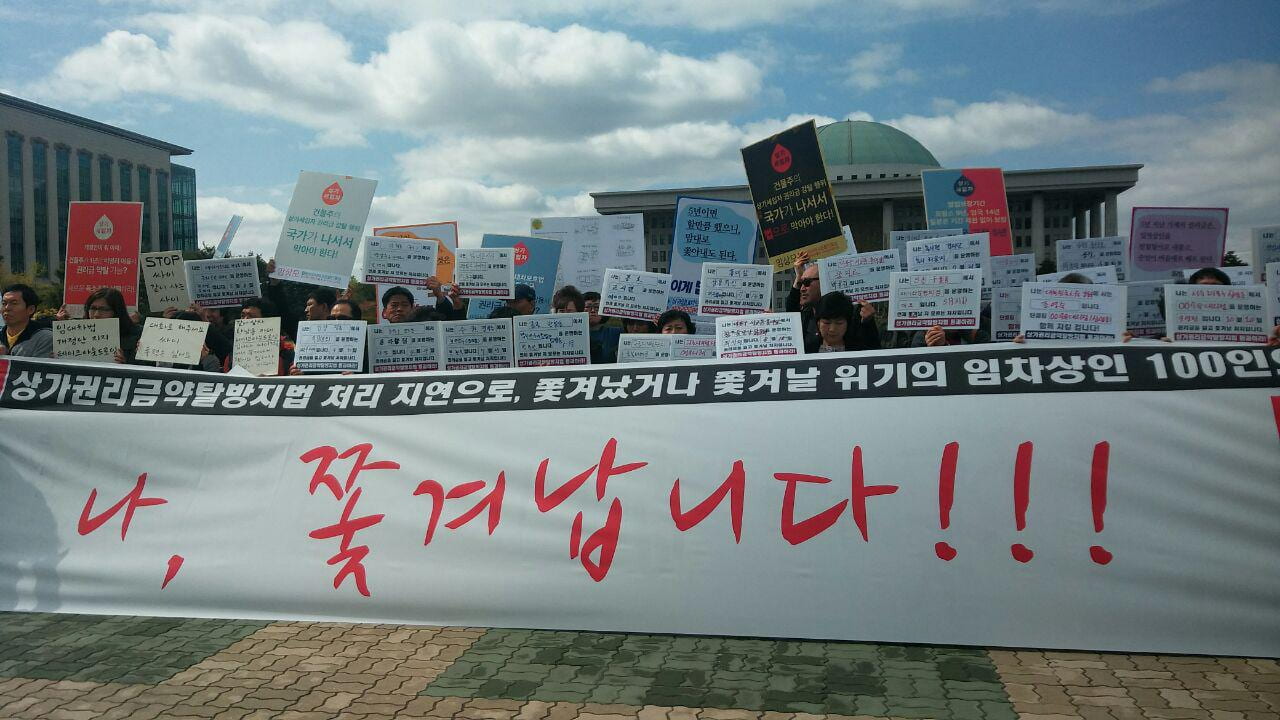

Yewon Lee is currently an Assistant Research Professor of International Affairs and Postdoctoral Fellow at The George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies (GWIKS). She received her PhD in Sociology at UCLA in 2019 and previously held a 2019-2020 Korea Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Toronto. Her current book project, entitled Precarious Workers in the Speculative City: The Untold Gentrification Story of Tenant Shopkeepers’ Displacement and Resistance in Seoul, examines how tenant shopkeepers challenge financial speculation in Seoul’s commercial real estate industry through protest and collective organizing. Dr. Lee’s research on the resistance to commercial gentrification in Korea has appeared in Critical Sociology. The manuscripts emerging from this research project have been well received, winning many prestigious awards, including the American Sociological Association’s 2020 Labor & Labor Movement Section’s Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Graduate Student Paper Award.

Yewon Lee is currently an Assistant Research Professor of International Affairs and Postdoctoral Fellow at The George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies (GWIKS). She received her PhD in Sociology at UCLA in 2019 and previously held a 2019-2020 Korea Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Toronto. Her current book project, entitled Precarious Workers in the Speculative City: The Untold Gentrification Story of Tenant Shopkeepers’ Displacement and Resistance in Seoul, examines how tenant shopkeepers challenge financial speculation in Seoul’s commercial real estate industry through protest and collective organizing. Dr. Lee’s research on the resistance to commercial gentrification in Korea has appeared in Critical Sociology. The manuscripts emerging from this research project have been well received, winning many prestigious awards, including the American Sociological Association’s 2020 Labor & Labor Movement Section’s Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Graduate Student Paper Award.